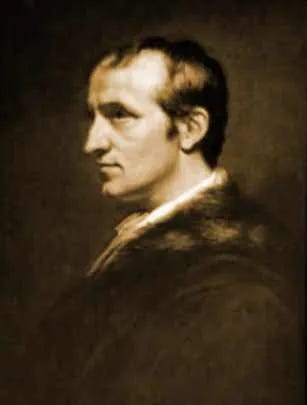

William Godwin – Founder of the English Enlightenment

"Nothing that is morally wrong can be politically right"

Journalist, political philosopher and novelist William Godwin (1756 – 1836) was hugely influential on a small group of thinkers who would form the basis of the English Enlightenment.

He significantly influenced various individuals and movements including Thomas Paine, Romantic poets like Wordsworth and Coleridge, as well as figures like Percy Shelley, the anarchist Peter Kropotkin and even Marx and Engels.

His utopian and idealist concepts also impacted on socialists like Robert Owen and William Thompson and influenced later working-class movements including the Chartists.

Born into the Dissenting tradition, he supported individual liberty, social justice and railed against the corrupting influence of government.

Married to Mary Wollstonecraft, the early feminist and mother of the writer Mary Shelley, Godwin was also a supporter of women’s rights and against colonialism and slavery.

In 1793 he published An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice as an attack on political institutions and a universalist plea for a classless society at a time when many were profiting from the transatlantic slave trade: “The rights of one man cannot clash with, or be destructive of, the rights of another. If one man have a right to be free, another man cannot have the right to make him a slave”.

Within 12 months he had published Things as They Are; or, The Adventures of Caleb Williams, an early mystery novel which popularised the ideas presented in Political Justice to show how legal and other institutions can destroy individuals.

Many establishment critics saw the book as anarchist propaganda which attacked the political and legal order and that Godwin was effectively spreading his "evil" principles throughout society.

William Godwin chose the date of publication as 12 May 1794, the same day the Prime Minister had suspended habeas corpus to begin mass arrests of suspected radicals.

This reality was therefore a description of ‘things as they are’, a title which may have influenced the title of Anthony Trollope’s masterpiece The Way We Live Now, a similarly satirical and political novel published in 1875 (subject of another Captain Swing substack).

Despite Godwin’s extreme revolutionary outlook, he had no sympathy with insurrection or violent revolutionary action and believed that the spread of enlightenment ideas could only be achieved through reason and persuasion.

He came from a long line of non-conformists who faced religious discrimination by the British government and was inspired by his grandfather and father to take up the dissenting tradition and become a minister himself.

At eleven years old, he became the sole pupil of Samuel Newton, a hard-line disciple of Robert Sandeman. Although Newton's strict manner left Godwin with a lasting anti-authoritarianism, Godwin absorbed the Sandemanian creed, which emphasised rationalism, egalitarianism and consensual decision-making which he held responsible for his commitment to rationalism and his stoic outlook.

Following the outbreak of the American Revolution in 1776 and after reading the works of Jonathan Swift he became a staunch republican. Godwin familiarised himself with the French philosophers, learning of Jean-Jacques Rousseau's belief in the inherent goodness of human nature and opposition to private property.

In Political Justice he argued that private property led to inequality and injustice. He advocated for a system where resources were distributed based on need, suggesting a form of communism as the ideal.

Following the outbreak of the French Revolution, William Godwin also lost his faith in an ‘intelligent God’ and became an atheist influenced by conversations with the poet and writer Thomas Holcroft.

Godwin joined the Revolution Society and met the political activist Richard Price, whose Discourse on the Love of Our Country espoused a radical form of patriotism that controversially upheld freedom of religion, representative democracy and the right of revolution.

This ignited the infamous pamphlet war between Burke and Paine, beginning with Edmund Burke's publication of his Reflections on the Revolution in France, which defended traditional conservatism against the ‘swinish multitude’.

In response to Burke, Thomas Paine published his Rights of Man with the help of Godwin, who declared that "the seeds of revolution it contains are so vigorous in their stamina, that nothing can overpower them”.

Despite the growing government suppression of British Jacobin support for the French revolution, Godwin's work was seen by many as a middle way between the extremes of Burke and Paine.

Prime Minister William Pitt famously said that there was no need to censor Political Justice, because at over £1 it was too costly for the average Briton to buy.

However, a growing number of ‘corresponding societies’ hungrily absorbed Political Justice, either sharing it or having it read to illiterate members. Eventually, it sold over 4,000 copies and brought Godwin brief literary fame.

In later years, Godwin was no longer seen as a threat and was awarded a sinecure position overseeing the sweeping of the chimneys of the Houses of Parliament. On 16 October 1834, a fire broke out and most of the Palace of Westminster burned down, it is still not clear what role Godwin played in the disaster.